Guide to African American History & Culture in Washington, DC

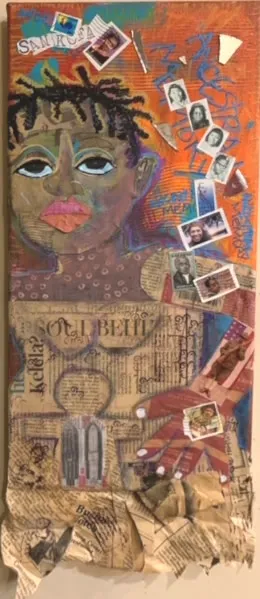

With its Southern connections, Washington, DC has always had a significant African American population. Before the Civil War, the city was home to a growing number of free Blacks who worked as skilled craftsmen, hack drivers, businessmen and laborers, and slave auctions were outlawed altogether in 1850. All slaves owned inside the city were emancipated on April 16, 1862. Since then, DC has remained home to a large African American population that has created vibrant communities and shaped the city’s identity as a culturally inclusive and intellectual capital. The influence of African American culture is undeniable as you make your way through the District. We’ve laid out must-see locations to help you take in this vibrant heritage and history. Historic Sites & Museums “Without a struggle, there can be no progress.” – Frederick Douglass Start your exploration with a visit to the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Community Museum. Located in the historic African American neighborhood southeast of the U.S. Capitol called Anacostia, the museum houses a collection of approximately 6,000 objects dating back to the early 1800s. The history of this neighborhood – home to orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass – is directly tied to the museum. Speaking of Frederick Douglass: make sure to visit the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, located at his former home, Cedar Hill. Tour this 21-room Victorian mansion, learn of Douglass’ incredible efforts to abolish slavery and take in one of the city’s most breathtaking views. Make your way to the National Mall, where you’ll find two of DC’s most prominent enduring monuments to African American history and culture. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial sits on a four-acre site and features a 30-foot statue of Dr. King that displays words from his famous “I Have A Dream” speech. The moving memorial also displays a 450-foot long Inscription Wall with 14 quotes from King’s unforgettable speeches, sermons and writings. In September 2016, the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture opened its doors a short walk away from the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial. This eight-story building, with a stunning exterior that features a three-tiered, bronze-colored screen, focuses solely on African American life, art, history and culture, covering artifacts from the African Diaspora to the present day. Admission to the museum is free, but has been in extremely high demand since the facility opened its doors and timed passes are required on certain days. From September through February, timed passes are required only on weekends and are made available online three months in advance. On weekdays, visitors can enter the museum without passes beginning at 10 a.m. During peak season (from March through August), timed passes are required on weekdays before 1 p.m. and on weekends. For full details, please visit the museum passes guide. Journey to the U Street neighborhood next, where you’ll find the African American Civil War Memorial. Appropriately located near the Shaw neighborhood (named after Robert Gould Shaw, the white colonel of the all-Black Massachusetts 54th Regiment), the memorial is a sculpture that commemorates the 200,000-plus soldiers that served in the U.S. Color Troupes during the Civil War. The nearby museum features exhibits, stories and educational programming that build on the powerful message of the memorial. Last but not least, follow Cultural Tourism DC’s African American Heritage Trail to see more than 200 significant sites rich in local Black history, from churches and schools to famous residences and businesses. Music & Entertainment “Music is what I hear and something that I live by.” – Duke Ellington DC served as the starting place for some of music’s greatest figures, including jazz great Duke Ellington, R&B legend Marvin Gaye and the godfather of go-go, Chuck Brown. Their legacy is prominent, as the District remains a hotbed for grooves. Once known as “Black Broadway,” the U Street neighborhood is a perfect place to start your dive into the District’s rich musical history. Twins Jazz is a prime spot to kick back and enjoy smooth sounds. The U Street Corridor also features the Howard Theatre. Its stage hosted the likes of Duke, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong in its 20th-century heyday, and now it boasts some of the best names in underground and popular music. Lincoln Theatre, also a historic hot spot for jazz, similarly features marquee names throughout its calendar. A cab ride to Georgetown to check out Blues Alley is also recommended – this jazz club has been standing for over fifty years. Finally, it never hurts to peep the schedules of other popular DC music venues like the 9:30 Club, Black Cat and The Hamilton Live to see who’s performing while you’re in town. Chuck Brown’s go-go music still thrives in DC, and you can pay homage to the legend at Chuck Brown Memorial Park in Northeast DC. Just as the music of Marvin Gaye still resonates, so does his impact on DC. Tap into some creative mojo by visiting Marvin Gaye Park – the singer used to sit by the stream on the east end of the park and write songs. We also recommend dining at Restaurant Marvin on 14th Street, decorated with images of the legendary singer and sporting an American/Belgian menu in honor of Gaye’s excursion to Belgium in 1981. If you’re interested in taking some of DC’s musical history home with you, the city has a litany of record shops where you can browse for jazz, go-go and R&B classics, among other genres (ask employees to point you in the right direction). Som Records on 14th Street lets you sample before you buy, while a jaunt down 18th Street will take you to Crooked Beat Records and Smash!, while Hill & Dale Records in Georgetown is also an option. Be sure to check out all the different ways to celebrate African American history and culture in Washington, DC.

Q&A with Mrs. Virginia Ali, Matriarch of Ben’s Chili Bowl

What keeps a restaurant open for more than 65 years? What is it that draws national attention to a neighborhood eatery? What magnetic force can possibly be behind the amount of love and dedication that this city (this coast, this country) feels for Ben’s Chili Bowl and its half-smokes? Certainly one factor is its location on U Street – once known as DC’s Black Broadway – and the symbol of community Ben’s became as the city prevailed through segregation, the societal upheaval of the 1960s and ensuing decades of drastic change in the neighborhood. But the leading reason Ben’s has grown to be an institution in the nation’s capital is its people. The restaurant’s dedicated staff is led with heart by Virginia Ali, the widow of Ben, with whom she cofounded the restaurant when she was just 24 years old. Virginia is approaching 90 years old, yet she remains a walking lesson in warmth and hospitality. She wants every customer to feel at home and thanks to her smile and a pat on the back, everyone does. It’s clear that she’d give you whatever you needed to feel comfortable and cared for. You can begin to see why Martin Luther King, Jr., for one, chose to spend many of his DC lunchtimes at Ben’s, and why the restaurant stayed open and served meals during the riots on U Street after the civil rights leader was assassinated. In the week leading up to the March on Washington’s 60th anniversary, we had the chance to talk to Virginia about MLK and other Ben’s lore: Ben’s arrived on the scene, in a segregated country, five years before the March on Washington. What did DC feel like to you during those five years? VA: In 1958, I left Industrial Bank (where I’d worked since 1952) to open the restaurant. We were going through the civil rights movement down south. Washington had begun to open up a few places to be integrated. And it was after the March that we passed the Civil Rights Bill. The March was on August 28, 1963. And the Uprising [the assassination of Dr. King] took place five years later. Has Ben’s been integrated since it opened? VA: Of course! We were never the prejudiced people. White people could go wherever they wanted. If they’d gone to the Howard Theatre to see one of our big entertainers, there’d be a whole bunch of white people [in the restaurant after]. To put it in perspective, behind me, if you walk to the end of this alley, around that circle where those beautiful townhouses are, it was Children’s Hospital. Children’s Hospital! Which had all kinds of doctors and lawyers and everybody running down here for lunch. You know what I mean? Thompson’s Dairy was one of the big businesses in the community that delivered milk to my house every day. … Smith’s Storage right up the street; C & P [Chesapeake and Potomac] Telephone Company was in the area … so there were large businesses here. That brought everyone together? VA: Yeah. We all lived together. Do you remember any specifics from interactions with MLK? VA: Well, I do remember one: one day we were talking and he said he’d had a meeting with President Kennedy. And with Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph and young John Lewis, and I don’t remember who else. And he had told President Kennedy, in order to bring attention to these injustices to Black people, he was going to bring a large group of protestors here. And he told me President Kennedy said to him, “I don’t think that’s a good idea. Because if you bring a large group of people here, and there’s an incident, it will set your movement back, Dr. King.” Dr. King said, “There will be. No. Incident.” Wow. VA: He brought 250,000 people. A sea of people. Did you attend the March? VA: Ben and I were there. A sea of people. And not a single incident. Just a very inspiring, beautiful day. And the very next year, guess what happened? They passed the Civil Rights Bill. The very next year. Do you have ideas about making more progress in America? VA: You know, the way I’ve operated my business certainly came from the teachings of my dad, my mom, from my home growing up. The way we lived. And that philosophy was: always, always, treat people the way you want to be treated. All people. Whether it’s the president, the judge, the guy on the corner, whatever it is – just treat all people the way you would like to be treated. And if you do that, you don’t have a problem. It’s that simple. It’s not rocket science at all. And it doesn’t take anything to do it but kindness. Ben’s is celebrating its 65th anniversary. It’s amazing to see such a happy story has lasted for so long. Do you ever think about what you would have done if there had never been Ben’s Chili Bowl? VA: No. And I do know that I love what I do. And when people came to me and said, “Are you going to stay here? Why didn’t you open someplace else?” I said, “This is the nation’s capital! It’s got to get better, right?” It’s got to get better. We are the nation’s capital. Check out Ben's Chili Bowl next time you're in DC. And if you want a taste of Ben's at home, order nationwide today.

QA Test Automated cron Article sync 1

As you return to traveling this year, Washington, DC should be at the very top of your list. The nation’s capital offers more than 100 free things to do, but it should come as no surprise that museums are some of the most popular attractions. We’ve gone into deep detail on four of the city’s most popular museums (including one dedicated to living animals), none of which charge admission. Find the latest updates on visiting museums, including Smithsonian's plans to have all of its museums open by the end of August 2021, mask mandates for all indoor museums and the latest ticketing requirements. Book your next vacation to the nation’s capital and visit these only-in-the-District museums, free of charge. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category. In the heart of the nation’s capital lives a portal to wildlife from around the world. Smithsonian’s National Zoo offers a firsthand, family-friendly experience through a 163-acre urban park in the Woodley Park neighborhood teeming with roughly 2,700 animals that represent more than 390 species. The zoo is also connected to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (a non-public facility located in Front Royal, Va.), a global effort to conserve species and train future conservationists. This focus on preserving endangered animals extends to the zoo, as one-fifth of its exhibited species fall into this category.